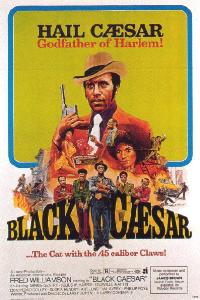

I ve previously expressed my admiration for the work of B-movie director Larry Cohen, a filmmaker who has always been very adept at making entertaining movies out of ridiculous premises. He is primarily known for his work in the horror genre with such films as It’s Alive, Q: The Winged Serpent, The Stuff and God Told Me To, but believe it or not, Cohen started off his directorial career doing blaxploitation pictures. After spending most of the 1960s as a television writer, Cohen finally stepped behind the camera in 1972 to direct Bone, a low-budget comedic thriller about a black man breaking into the home of a wealthy Beverly Hills couple and taking them hostage. However, the film that really put Cohen on the map was his follow-up, Black Caesar. Surprisingly, this is not a Larry Cohen film based around an off-the-wall premise, but instead features one of the oldest rise-and-fall stories known to man. This could probably be classified as one of the most unusual remakes of all time as Black Caesar is pretty much a modernized blaxploitation version of the 1931 gangster classic, Little Caesar. That film featured Edward G. Robinson in a star-making performance as a young hoodlum who rises through the ranks of organized crime to become the biggest gangster in the city, but is so corrupted by power that he eventually suffers a catastrophic downfall. Black Caesar essentially tells the same story, except that it’s set in 1970s Harlem and the main character is played by NFL-star-turned-blaxploitation-star Fred “The Hammer” Williamson. Like much of Larry Cohen’s work, Black Caesar is not exactly a model of polished filmmaking. It’s cheap, crude and sloppily assembled, but it’s very entertaining and tells its age-old story quite well.

Black Caesar opens in Harlem in 1953 with a terrific sequence where an African-American kid named Tommy Gibbs offers to shine the shoes of a local gangster. However, this all turns out to be a ruse as Tommy holds down the gangster’s foot, allowing him to be assassinated by a rival mobster. This marks young Tommy’s initiation into the world of organized crime, but is confidence is quickly shattered when he suffers a beating at the hands of a corrupt racist cop named McKinney (Art Lund). This incident ensures that Tommy will forever have a chip on his shoulder and when we are finally introduced to grown-up Tommy (Fred Williamson), he is beginning his climb to the top of the New York City underworld. He starts off by assassinating a gangster who has an open contract out on him and while the Italian mafia are not exactly thrilled to have a black guy doing a hit for them, they eventually welcome him into their inner circle. However, Tommy is none-too-thrilled about the prospect of working for white folks, so it isn’t long before Tommy double-crosses the Italians and builds up his own black crime syndicate to take over Harlem. The biggest piece of leverage Tommy has to keep himself safe are some stolen ledgers. They contain a record of all the financial transactions between the mafia and corrupt politicians and policemen, including McKinney, who has now become a powerful police captain. Tommy Gibbs becomes the godfather of Harlem and is beloved by the black community, who are happy to have one of their own in such a powerful position. The film contains a wall-to-wall soundtrack of kick-ass James Brown music, which always follows Tommy around whenever he walks down the street.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ngajzGJlkSM

Of course, power and money only wind up corrupting Tommy Gibbs in the long run and eventually lead to his downfall. This is perfectly symbolized by a scene where Tommy buys a luxurious penthouse apartment for his hard-working mother, who is less-than-happy about the illegal means in which he obtained it. It gets to the point where Tommy winds up alienating everyone around him, most especially his wife, Helen (Gloria Hendry), who conducts an affair with Tommy’s best friend. Tommy had such a deep-seated hatred for McKinney and he powerful white people that he soon pushes them too far. McKinney devises a plan to retrieve the stolen ledgers from Tommy, and most of Tommy’s associates are either killed or bought off, leaving him with no one to turn to by the end. This type of story has been done many times before, but in 1973, it was quite unusual to see it done with a black protagonist. The character of Tommy Gibbs appears to have been partially inspired by Frank Lucas, who was the godfather of Harlem at the time and eventually portrayed by Denzel Washington in American Gangster. Lucas may have been completely amoral, but he was still looked at as a hero by many members of the African-American community since it was so rare to have someone that powerful representing them and looking out for their interests. Black Caesar does not hesitate to paint Tommy Gibbs as a hypocrite who claims to be looking out for the interests of his community but, in the end, mostly just cares about himself. That said, Fred Williamson is so charismatic in the role that you still sympathize with Tommy and care about what happens to him. Black Caesar may be a crude, low-budget blaxploitation picture, but it’s still a very well-acted one. In addition to Williamson’s strong performance, he gets solid support from the likes of Art Lund as the reprehensible McKinney, Gloria Hendry as Tommy’s wife, D’Urville Martin as Tommy’s colourful sidekick, Reverend Rufus, and noted character actor Julius Harris as Tommy’s estranged father.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=1KE8uwje2hk

In spite of its serious dramatic intentions, Black Caesar is still a blaxploitation film at heart and Larry Cohen does not hesitate to hide its B-movie origins. The film’s standout scene is when Tommy is shot in the gut on a crowded New York City street and he tries to escape from his assassins in a taxi. The whole sequence of events is pretty absurd, but it is exciting. During the climax, Tommy gets revenge on the racist McKinney by rubbing shoe polish on his face and forcing him to perform a blackface routine, which makes for one the goofiest, yet hilarious comeuppances ever received by a villain. Viewers have also debated whether the ending of Black Caesar is too ridiculous and over-the-top, but I’ve always found it wonderfully ironic and appropriate for the material. In another ironic twist, the ending of Black Caesar was almost completely undermined when the film became an unexpected box office hit. The distributor suddenly requested that Cohen make a sequel, Hell Up in Harlem, and it wound up being completed and released into theatres only nine months after Black Caesar came out! Hell Up in Harlem is truly one of the most slapdash sequels you will ever see. Cohen and Williamson were already working on other projects when the order for a sequel came down, so they pretty much had to shoot all the footage and assemble everything together in their spare time. The end result is a hastily assembled mess, but like many of Cohen’s other films, it’s an entertaining mess. Black Caesar is not a perfect movie either, but its unprofessional look actually adds a level of realism and authenticity to many of the scenes. Considering its low-budget origins, it’s a lot better gangster movie than you would expect and still retains a lot of raw power. Even though films like Shaft and Superfly are often considered the cornerstones of the blaxploitation genre, Black Caesar is a superior film to them and just another interesting chapter in the very unique and diverse career of Larry Cohen.